A small notebook unearthed at Mittagong rubbish tip, in the NSW Southern Highlands, and detailing a Sydney couple’s real estate adventures is charming readers more than a century on.

Outwardly grubby and missing its cover, the notebook was donated to the State Library of NSW in 1984.

It sat among the bulging manuscript stacks in the library for decades until curator Margot Riley and a colleague stumbled across the rare gem while preparing for an event.

“I typed into the catalogue ‘house construction’ and up popped this record about a notebook,” Ms Riley, who wrote a blog post about the notebook earlier this week, said.

“We had never looked at it or seen it. The library has hundreds of thousands of pages of manuscripts and negatives.

“We ran downstairs to stack and there was this small blue box. We opened it up and inside – wrapped carefully in tissue – was this little book.

“It’s very unusual, I don’t think I have ever seen anything like it before.”

The notebook belonged to Carl Moore, an artist, and features colourful sketches of the home he and his wife Gertrude were planning to build.

It was 1913 – long before the days of Domain and the government’s $25,000 new HomeBuilder grant – but the couple still knew how to snare a bargain.

The couple purchased a subdivided piece of land in Hurstville for just under £100 on the corner of Belmore Road and Stanley Street (now King Georges Road and Australia Street).

In what would have been unusual for the time, Mrs Moore contributed £40 to the cost of the land.

In the notebook, Mr Moore meticulously sets out all the details of the transaction, even down to his trip to the bank and the serial numbers of the banknotes used to seal the deal.

In an entry on January 25, Mr Moore includes a sketch of the couple’s planned home, alongside the possible inclusions and how much they would cost.

For £180 pounds the couple could have their home without a verandah and also minus any internal doors and lining; for £260 they could have the lot.

But Ms Riley said it was the personal nature of the journal that made it so relatable.

“It talks about them going for wildlflower walks. They take their thermoses and deck chairs and they sit there and imagine what the house will be like when it is finished.

“They get to know the area and their neighbours and start to plant a garden and all of those things that people can relate to.”

The couple’s one-storey brick home is still standing today, with some adjustments, Ms Riley said.

“You can see on Google Streetview it’s still there and still the same house. The only thing is they have bricked in the front verandah,” she said.

With additional research and the help of the library’s followers on social media, Ms Riley said some facts about the couple’s future life had been pieced together.

The couple went on to have what appeared to be their only child, a daughter named Marie Gertrude, in 1918.

Mr Moore is thought to have died in Carlton in 1951, while his wife passed away 13 years later at the age of 80.

Ms Riley said the library was yet to hear from any descendants of the Moore family who might be able to shed some light on how the notebook came to be left at Mittagong tip.

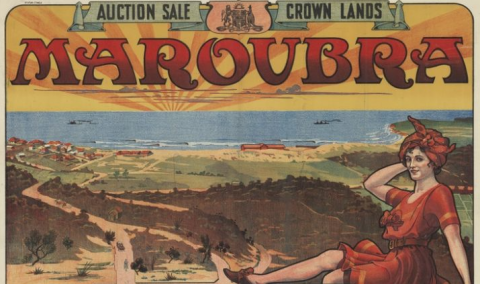

‘Running water and good soil’: How Sydney property was advertised a century ago

It’s hard to imagine, but there was a time when Bronte was a new suburb, Blacktown was the countryside and Vaucluse was considered affordable for a moderate-income home buyer.

Sydney real estate has unsurprisingly changed a lot since the days of the late 19th and early 20th century. Properties are no longer priced in pounds, and there aren’t vacant blocks aplenty waiting to be snapped up.

Cafes and a vibrant dining scene have long replaced good soil as a hot suburb attribute, and you’re unlikely to see electric light and running water proudly noted on real estate advertisements.

Far from the in-demand suburb Bronte is today, the seaside suburb was just starting to taking shape more than 100 years ago.

Subdivision plans

In the same decade, a block of land in the now affluent suburb of Vaucluse could be snapped up with a £5 deposit (approximately $430 in today’s terms).

A 1918 ad for Lock’s Seaview Estate on the South Head marketed the land as a“chance for a person of moderate means to acquire a home site fit for a millionaire”.

However if you did secure the “very cheap land” you had to construct a building that would cost no less than £250.

Around that time, a similar-sized deposit could get you a beachfront block in Bondi, which offered a “congenial climate”, or a property on the Pittwater at Church Point, which offered a deep water frontage.

As it was unreachable by public transport, the auctioneers offered to meet buyers at the Narrabeen tram stop and drive them to the Church Point site.

Meanwhile in Rose Bay, Hardie & Gorman and Raine & Horne were selling blocks from 45 shillings per square foot, and offering free stone to build new homes with.

By 1929, the western Sydney suburb of Blacktown also had subdivided blocks for sale for a £5 deposit.

While today it’s far from the city fringes, it was once dubbed as the suburb “where the city meets the country” which offered “plenty of space for vegetable and poultry, and the best soil in the district”.

Agents at the time were also keen to promote the health benefits that could come with buying away from the city centre.

“[Beecroft] is strongly recommended by the Medical Profession as being the most healthful as it is one of the most picturesque suburbs,” reads a 1915 advertisement for the first subdivision of Eaton Park.

More than 30 years later, blocks in Bronte were still available, being sold through Richardson & Wrench, who (assuming all buyers would be male) described them as “the foundation for a long, healthy life for yourself, wife and family”.

Buyers in 1915 were urged to get in quick if they wanted a block with “a nice slope sufficient for drainage purposes” in the once barely known suburb with shade trees and tea houses, which was becoming increasingly popular.

How Melbourne real estate was advertised a century ago

Back when St Albans was a new suburb and Brunswick was still paddocks, you could find Melbourne’s real estate spruikers pitching the advantages of “perfect drainage” and a lack of “noxious trades” in a suburb.

It’s a stark contrast to real estate listings today, which proffer sought after school zones, state-of-the-art kitchens and vibrant cafe scenes to get buyers on board.

Thousands of highly-decorative auction posters were made in the late 1800s and early 1900s to advertise allotments, including colourful illustrations, decorative fonts, exaggerated claims and even verses.

They paint a quaint picture of how real estate was sold a century ago.

Today houses are sold in dollars not pounds, the distance from the CBD is measured in kilometres rather than miles, and inner-city vacant blocks are sold for millions.

But some things continue to be as relevant for buyers today, as they were 100 years ago: proximity to shops, train stations and parklands. Some posters even refer to railway stations or tram lines that were never built.

In contrast to the trendy inner-northern suburb people are familiar with today, Brunswick was depicted full of paddocks and livestock more than 100 years ago. An auction poster advertising lots in Brunswick’s Moorabinda estate – bordered by Sydney Road, Stewart Street, Lygon Street and Blyth Street – featured a bushranger-type character riding a horse into the unknown and a poetic verse. The allotments were asking for a £5 deposit.

Banking historian and retired professor at Melbourne University, David Merrett, said buyers in the past may have had to approach lenders such as building societies because banks did not lend for housing purchases before the 1950s.

“The State Bank of Victoria was an exception. However, its lending for new dwellings was of little help to the poor,” he said. “The minimum loan was £1000, the maximum length of the loan was three years and the amount you could borrow was no more than three-fifths of the banks’ valuation of the house. The restrictions were relaxed somewhat after 1911 and for ex-servicemen but it was not easy.”

Mr Merrett said the State Bank of Victoria had “unbelievably stringent rules” for a loan to be approved to build a house. The bank also had a book of plans buyers had to choose from and it also oversaw construction.

In nearby Coburg, an advertisement for lots in Moreland Park asked buyers to “inspect the pretty villas and family mansions” in colourful fonts. It featured a collage of sketches of period homes, peppered with notes such as “drainage perfect” and “water and gas”.

Buyers were also invited to consider Moreland Road, West Brunswick – described by its poster as “the land of promise”. It featured men in robes and phrases such as “a home for the chosen people” and “a paradise in miniature”. More than 160 allotments were available in “the most perfect sites of rural beauty to be found in Great Australia”.

It’s hard to understand why, but St Albans was apparently “the healthiest suburb of Melbourne”, only 22 minutes’ ride from town.

St Albans Historical Society president Ron Dorre said the suburb was built around the train station. He suspected the suburb was described as “healthy” because it was not an industrial area, whereas neighbouring Sunshine had a lot of industry with chimneys and smoke.

Meanwhile, many posters mentioned marquees, luncheons and passes for trams or trains.

“It’ll be a whole day trip to buy a piece of land in St Albans,” Mr Dorre said, adding that it was “a whole social occasion”.

“You’ll have to get the train in, have lunch – which they provided,” he said. “Now you would rock up at an auction, bid and then get in a car and drive off.”

Source: Emily McPherson, “Artist’s notebook reveals what Sydney’s real estate market was like a century ago”, January 20, 2021, 9News. Kate Burke, “‘Running water and good soil’: How Sydney property was advertised a century ago”, June 8, 2017, Domain. Christina Zhou, “How Melbourne real estate was advertised a century ago”, June 14, 2017, Domain.