After the big blast announcement in December 2023, the NSW Government has released more details on residential zoning changes designed to unlock the housing supply drought.

The State Government’s latest strategy has three main components, and will enhance the changes included in the Low Rise Housing Diversity Code which was introduced in 2018.

Transport Oriented Development Program

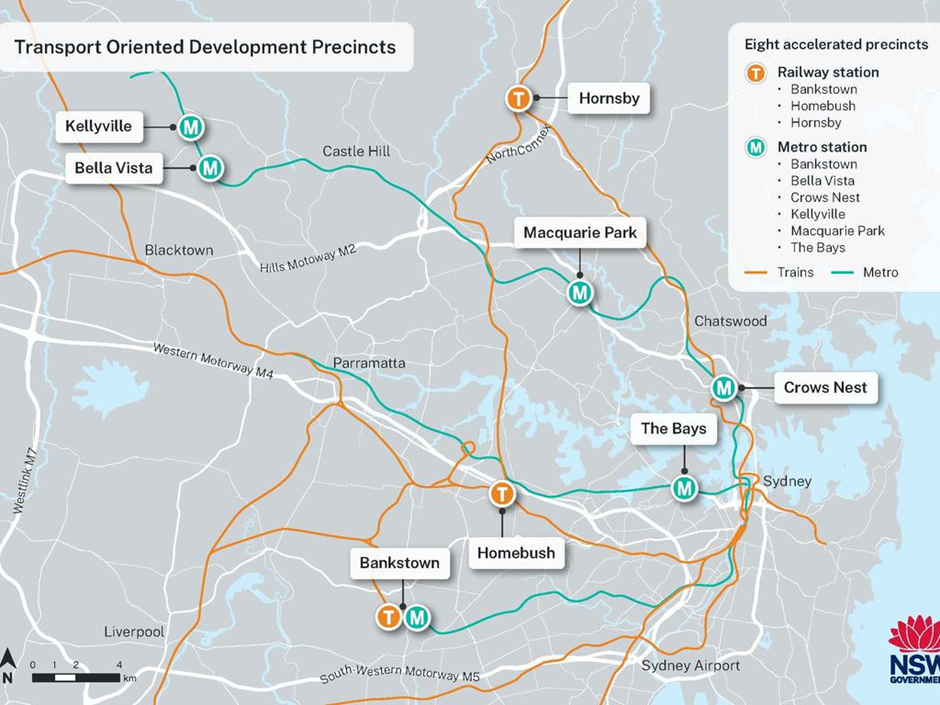

The first component of the new strategy is the Transport-Oriented Development (TOD) Program. The Program identifies eight transport hubs, referred to as Tier One sites, where accelerated rezoning could help deliver up to 47,800 new homes over the coming 15 years.

By the end of 2024, changes to planning permissions will allow more density in developments located within 1.2km of metro or train stations at Bankstown, Bays West, Bella Vista, Crows Nest, Homebush, Hornsby, Kellyville, and Macquarie Park.

Tier One transport-oriented development sites in Sydney.

Fifteen per cent of dwellings in approved developments must be affordable and available to key workers, like nurses, teachers and hospitality professionals, and construction must start within two years.

In addition, 31 other locations across the state will be ‘snap rezoned’ to allow greater densities within 400m of metro of suburban rail stops and town centres.

The idea is to create new homes in locations that have existing infrastructure such as Ashfield, Dulwich Hill, North Strathfield, North Wollongong, and Gosford.

Housing diversity

The second component of the government’s plan is to allow different types of homes in identified suburbs, for example flats / units, terraces and duplexes.

Each Council currently has its own rules on the types of dwellings permissible in their areas, and most don’t allow much flexibility. This means property owners are restricted to planning regulations that are often fifty or more years old.

The Minns Government is currently taking a collaborative approach to introducing the changes but if Councils don’t fall into line, it is expected the State Government will enforce the State regulations in a bid to address the housing crisis.

In the coming months, a ‘pattern book’ containing pre-approved designs for the extended range of housing types will be available as a further measure to support fast-tracking development activity and make it easier for property owners to understand the new requirements.

Funding commitments

The third prong of the State Government’s TOD Program sees $520 million allocated for community infrastructure projects in Tier One locations to support the extra density, such as public open spaces and road upgrades.

NSW State Premier, Chris Minns, has described the sweeping reforms as ‘modest’ given what’s at stake.

“We can have a modest change to the amount of people or houses that we build each year, and over time it can make a massive difference to the cost of housing,” he said.

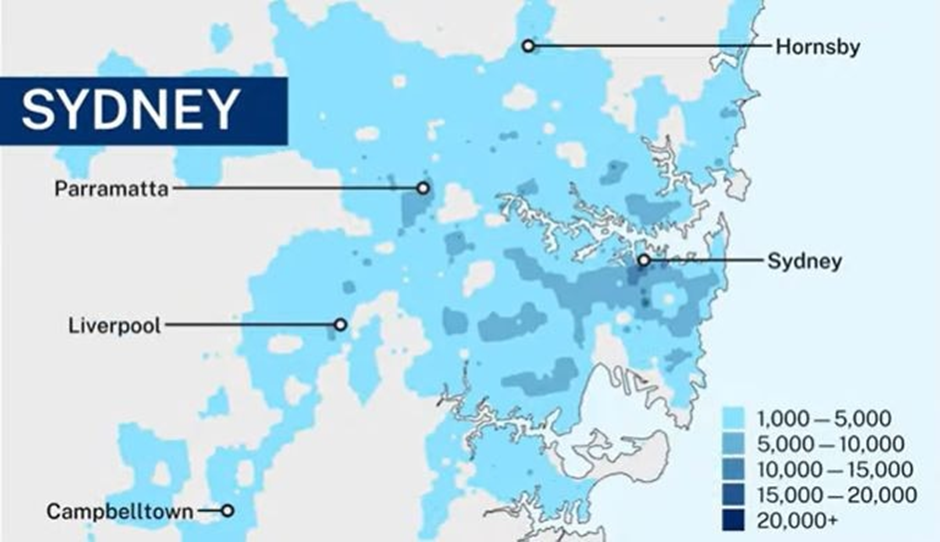

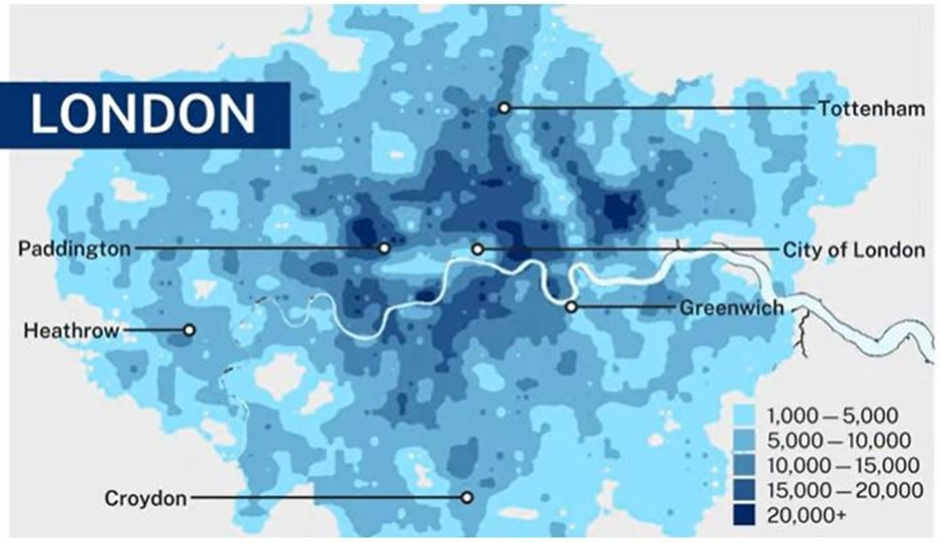

When compared to other major capitals around the world, Sydney is considered to have opportunities to increase housing while still being a long way from being overcrowded. Cities such as New York and London have much higher density, however they also have a much more efficient transportation and more extensive general infrastructure such as hospitals and schools.

Map showing density levels in Sydney.

Map showing density levels in London.

Not everyone is onboard

At least two Labor Councils have expressed opposition to the plan, arguing it could reduce living standards for residents by oversimplifying the current rules.

Inner West Council and Canterbury Bankstown Council have taken aim at the State Government plan, saying the reforms will have “major implications” for their residents and have hinted a legal challenge could be launched.

Sydney’s missing 45,000 homes

The State Government has cited the low supply of housing as the impetus for the zoning changes, and the cost of doing nothing was made abundantly clear in a recently released Productivity Commission report.

According to the report, an extra 45,000 dwellings could have reasonably been built over the five years from 2017 to 2022 with no extra land required, by allowing higher buildings in key areas.

The Government states the extra dwellings could have seen prices and rents 5.5 per cent lower – $35 a week for the median apartment, or a saving of $1800 a year for renters.

Low rise housing diversity code

The extra rezoning will enhance the Low Rise Housing Diversity Code. Released in 2018, the Code hasn’t been fully embraced or actioned by many Councils across NSW.

Originally introduced to fast track housing supply in established centres, under the Code duplexes, terraces and manor houses can be approved as complying developments in as little as 20 days, skipping the development application process.

In addition, residential blocks now only need to be 12 metres wide for a duplex, overriding existing Council rules requiring frontages to be at least 15 to 20 metres.

Most suburban homes across Sydney will be affected by the new regulations. The changes could see thousands more humble cottages bulldozed to build duplexes, with homeowners across Sydney who sell their properties to developers set to see significant windfalls.

Property market specialists have estimated a property suitable for a duplex, also known as a dual occupancy, would be worth about 20 per cent more than a property where a duplex can’t be built – and depending on the area it could even mean duplex-friendly blocks command a premium of up to 30 per cent.

That means a median-priced Sydney house that was once deemed too narrow for development could potentially rise in value by almost $240,000.

Although duplex-friendly development sites are expected to become more expensive, changes to the planning code would be a big advantage for Sydney’s housing shortage.

This means there is a definite upside for developers, but at the same time, mum-and-dad landowners can now have the flexibility to utilise their block and potentially build a new home for themselves and have a second property beside them with rental return.

In NSW the average turnaround of a development application is 71 days, but in many cases it can take more than a year for a project to be approved.

It is hoped the changes will make the planning process more efficient, and ideally less time-consuming, which will make actioning a development more attractive to a lot more people.

Blocks will still need to meet the minimum block size required for a dual occupancy by Council, usually 500 or 600 square metres. But if no minimum is specified under the Council’s local environmental plan, blocks only need to be 400 square metres to meet the State Government planning requirements.

According to NSW State Planning, increasing the State’s amount of medium-density housing will provide an opportunity for seniors to downsize as well as offering a more affordable option for young people when renting or buying their first property.

What qualifies a property for redevelopment into a dual occupancy?

The Low Rise Housing Diversity Code applies to R1, R2, R3 and RU5 zones across NSW, but most residential lots in Sydney fall into these zones. Designs must also meet the relevant design criteria in the Low Rise Housing Diversity Design Guide.

Dual occupancies can now be approved as a complying development providing they meet certain standards.

- Blocks must be at least 400 square metres, or the minimum lot size according to Council, whichever is greater.

- Blocks must be at least 12 metres wide. For dual occupancies where one dwelling is located above another, the block must be at least 15 metres wide.

- Buildings must have a minimum side setback of 0.9 metres. Greater setbacks apply for blocks wider than 24 metres.

- Each dwelling must be at least 5 metres wide and can’t be more than 8.5 metres high.

- Each dwelling must face a public road, and can’t be located behind another dwelling except on a corner lot.

- Each dwelling must have at least one off-street parking spot.

- Dual occupancies must be permitted on the land under the council’s local environmental plan.

What qualifies a property for redevelopment into terraces?

Under the new code, terraces are defined as three or more separate dwellings built side by side on one lot, with each dwelling facing the street.

- Blocks must be at least 600 square metres, or the minimum lot size according to Council, whichever is greater.

- Blocks must be at least 18 metres wide.

- Buildings must have a minimum side setback of 1.5 metres.

- Each dwelling must face a public road, and can’t be located behind another dwelling.

- Each dwelling must be at least 6 metres wide and can’t be more than 9 metres high.

- Each dwelling must have at least one off-street parking spot.

- Attached dwellings must be a ‘permitted’ land use under the Council’s local environmental plan.

What qualifies a property for redevelopment into a manor house?

A manor house is a two-storey building that contains three or four dwellings under the one roof, designed to appear as an oversized double-storey house from the street. According to the low rise housing diversity design guide, manor houses are best suited to corner lots or those with rear lane access.

Each dwelling can be subdivided and strata titled to allow separate ownership, effectively creating a small apartment block.

- Blocks must be at least 600 square metres.

- Blocks must be at least 15 metres wide.

- Buildings must have a minimum side setback of 1.5 metres.

- Each dwelling must have at least one off-street parking spot and one secure bicycle storage space.

- Each dwelling must have a minimum internal floor area:

- Studio – 35 square metres.

- One bedroom – 50 square metres.

- Two bedrooms – 70 square metres.

- Three or more bedrooms – 90 square metres.

- Manor houses must be a ‘permitted’ land use under the Council’s local environmental plan.

Reference : NSW State Environmental Planning Policies

About the author

Debra Beck-Mewing is the Editor of the Property Portfolio Magazine and CEO of The Property Frontline. She has more than 20 years’ experience in buying property Australia-wide and has extensive experience in helping buyers use a range of strategies including renovating, granny flats, sub-division and development. Debra is a skilled property strategist, and a master in identifying tailored opportunities, homes and sourcing properties that have multiple uses. She is a Qualified Property Investment Advisor, licensed real estate agent and also holds a Bachelor of Commerce and Master of Business. As a passionate advocate for increasing transparency in the property and wealth industries, Debra is a popular speaker on these topics. She is also an author, podcast host, and participates on numerous committees including the Property Owners’ Association.

Follow us on facebook.com/ThePropertyFrontline for regular updates, or book in for a strategy session to discuss your property questions.